Read it and weep

I've found this summer's tear-jerker

NEWSFLASH July’s Backstory events are now on sale. It’s a sizzling summer line-up, featuring chef José Pizarro, Liverpool FC’s former research director Ian Graham on how to win the Premier League, Private Rites author Julia Armfield, Ita O’Brien — the intimacy co-ordinator for Normal People and Sex Education — and Horatio Clare on the small boat crossings, in an event for which we’re donating all ticket revenue to Wandsworth Welcomes Refugees. Snap up your tickets now.

“IT GIVES ME NO PLEASURE,” a friend wrote on a WhatsApp thread of old uni friends the other day, “to report that Tom has made me cry on the tube three times in two days”.

Guilty as charged, I’m afraid. She had, it turned out, finally got around to reading our excellent 2023 Book of the Year, Alice Winn’s In Memoriam. (If you haven’t read it yet, where have you been? In the three years I’ve run Backstory, it’s the book that’s stuck with me most.) Now she professed herself “devastated”.

Well sorry Megan, but I’m about to devastate you — and other readers of this newsletter — all over again.

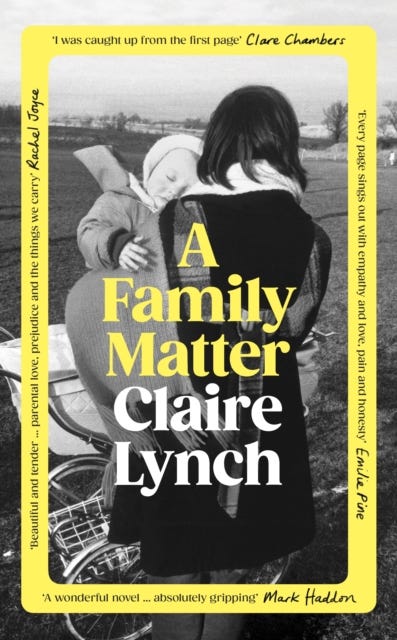

Perhaps we should hand out tissues instead of bookmarks with every copy we sell of Claire Lynch’s debut novel, A Family Matter.

It’s the, well, devastating story of a woman in a humdrum marriage in the 1980s whose lesbian affair has the most horrific implications for everyone involved — not least her young daughter — thanks to the cruelty of the state and judiciary’s attitude at the time.

I could go on, but I thought I’d leave it to the author herself, who has written an exclusive piece for this newsletter on the book’s, ahem, backstory.

Tom

My debut: the backstory

Claire Lynch

My debut novel, A Family Matter, opens in 2022 with Heron, an older man who has just been given a terminal diagnosis. For the past forty years Heron has raised his daughter, Maggie, alone. Although their relationship is very close, in this moment of personal crisis, Heron chooses not to tell his daughter the truth, about his illness, or their shared past. In the novel’s second timeline, 1982, we come to understand exactly why Maggie’s mother, Dawn, has been missing from the family for all these years.

In some ways, the historical context for the novel snuck up on me. I understood, in a general sense, that a young mother falling in love with another woman in 1982 would have been taboo. I did not know that the consequences could be so brutal, or so official. My research took me to a number of sources: queer community archives, national newspapers, PhD theses, and legal documents.

Reading the transcripts of judges’ reports I was able to form a clearer picture of how someone like my character Dawn would have been treated by the courts. It is still shocking to put into words that in Britain in the 1980s, 90% of lesbian mothers taken to court lost custody of their children.

All of the factors we might imagine to matter most in a child custody case — the wishes of the child, say, or their health and happiness, the stability of their home environment — were seen as irrelevant. A lesbian mother was an oxymoron. By very definition, she was simply unsuitable to be a mother at all.

Understanding this as historical reality was one thing, but my job as a novelist was to translate these cases into the lived experience of my characters. One of the most powerful sources for this came in the form of the Lesbian Mothers’ Legal Handbook, written, collectively, by the Rights of Women Lesbian Custody Group and published by The Women’s Press in 1986.

The book is an utterly extraordinary piece of social history, capturing the full range of obstacles faced by lesbian mothers at the time. The writing is clear, urgent, and it is necessary. Even the text on the back cover sets out the book’s purpose with a sort of forceful straightforwardness:

‘Some lesbian mothers do get custody of their children, but many do not. This book informs lesbians with children about what precautions to take if they want to keep charge of their children…’

As the blurb suggests, the handbook is full of practical advice, guiding lesbian mothers on what to say (or not say) to their solicitor, a step-by-step guide for their day in court. It is also a profoundly moving book, in the way the authors prioritise the voices of the women and children who have learned, from bitter experience, the ‘precautions’ that must be taken to keep a family together.

Reading about these families gave me an uncanny sense of walking in someone else’s shoes, as if watching a life that might have been mine, but for the few decades which separated us.

I am not alone in this experience of finding inspiration in queer history. In recent years, Tom Crewe’s The New Life, with its exploration of the legal, social, and scientific attitudes to homosexuality in the late nineteenth century has mapped the writings of real historical figures onto fictional protagonists.

Alice Winn has given us the love between Henry Gaunt and Sidney Ellwood in her novel In Memoriam, following the characters from their schooldays to the trenches, taking inspiration from the history and the poetry of the First World War. Yael Van Der Wouden’s The Safekeep is as much about the aftermath of the Second World War in the Dutch countryside as it is about what happens in Eva’s house, or indeed her bed.

My copy of the Lesbian Mothers’ Legal Handbook arrived in bubble wrap and brown paper from an online bookshop specialising in out-of-print editions. The glue in the spine is drying out, pages are starting to come loose. I have made my own mark on the book too, with passages highlighted in neon yellow and green. Phrases which seemed important for my research, but also, I think, re-reading them now, words which leapt out at me as I read them in disbelief. In the chapter ‘In Court Strategies’, for example, readers are warned to:

‘Expect the father’s barrister to be as unpleasant as possible. The judge may also ask unpleasant questions and can overrule objections.’

The baldness of these warnings fed into my portrayal of the barrister and judge in the novel’s court scenes, but these lines also shaped the emotional landscape of the novel. As I used the handbook to develop my sense of the novel’s historical context, I was also deeply motivated to do justice to the real people who had lived through the events I was now mining for fiction.

Turning the pages of the legal handbook, I was struck by the sense that the last woman to have held this book in her hands may well have seen it not as a source of research, but as a desperately needed life ring. The very existence of the book, the fact that it was needed so recently, was a tipping point in my writing. It was irrefutable evidence that cases like these had happened, proof that the story needed to be told.

Want more Backstory?

Come to one of our events

Request a book to pick up in the shop (we can usually get a book for the next day)

Order a book from our website

Come on now, if you're gonna make people cry, you should make 'em laugh, too-- gotta keep 'em emotionally balanced, y'know?? 😅